Mexborough and Swinton Times March 18, 1938

Link With Old Swinton Industry

Potter’s Cottage Goes

Reminiscences of the Rockingham Era

A King’s Dessert Service

In the world of ceramic art the word ‘Rotherham’ need not be added to the address to prove Swinton’s prestige. “Mexborough”, and even `Yorkshire’ are needless additional definitions. For lovers, collectors, and vendors of pottery Swinton is known throughout the world.

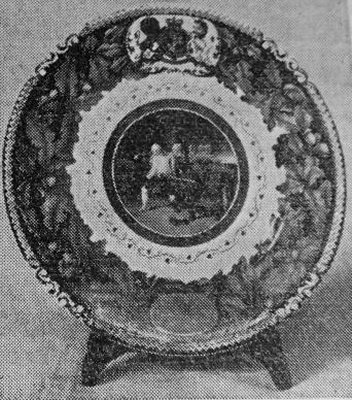

With good reason. Is there not, among the treasures of Buckingham Palace, a dessert service of 144 plates and 56 large pieces which William IV. bought for £5,000, and which bears the name ‘Swinton’?

And a hundred years ago was not Swinton pottery among the most cherished possessions of not merely the noble families of this country, but of the continent? And do not buyers at Christie’s still scan the back of ceramic works of art for the town’s name?

Forgotten?

All this Swinton folk seem to have forgotten. Otherwise they would scarcely have suffered a memorial to the days of their town’s highest artistic fame to have passed from sight, unsaluted, unhonoured, and until now unsung. For stone by stone Brameld’s Cottage has fallen to the picks and bars of demolition.

Only the foundations of the old cottage in which members of the Brameld family lived while they wrought to bring fame to Swinton now remain. The rest is rubble—and memories. The actual site on which the cottage stood is now to be part of the grounds of a house being, built for Dr. S. 0. Hatherly, near the Wath-Swinton boundary, opposite Warren Vale Road.

Last Occupant.

The last occupant of the cottage was Mr. Henry Harvey, who died last week at his daughter’s house in the Quarry Hill Road district of Wath

Mr. Harvey was 95 (the oldest man in Wath and Swinton) and he lived for more than 70 years in Brameld’s cottage.

One of his two daughters, Mrs Sykes, told me of her memories of the story cottage. He said it was a large house with thatched roof and diamond-shaped pains in the window. She believes it was converted from stables. There were three doors which were exquisitely carved to represent woodland scenes.

“I understood” she said, “that these carvings were the work of Italian painters who the Brameld’s at one time employed.

“I remember, when I was very young, the large wine cellar was full of bottles containing liquid we did not know. These were thrown away.”

When I was talking Mr old Mason of High Street, Rotherham one of the accepted authority in Rockingham ware I mentioned this fact and he agreed with me that perhaps in this way some of the Bramelds’ special preparation for use in the pottery were lost.

“Fox Hole.”

It would seem from legends current from old people of the district that at one time the Bramelds had to guard their precious pottery with great care, and I asked Mrs. Sykes if she could tell me anything, about a stone cave at the back of the ‘cottage which was used as a strong room”. She could not confirm the legend, but said a cave certainly existed and we always referred to as the “fox hole”. In addition she remembered very high wall that surrounded the use and garden.

Mrs. Sykes told me that as a child she broke many specimens of Rockingham ware and she well remembers finding scraps of the pottery when playing in the neighbourhood of the ponds near the old works. However, members of her family have still several good examples.

Incidentally, there is good ground for believing that at one time Mr. Harvey’s father, David, was a handle-maker employed by the Bramelds.

The Mason family of Rotherham have a considerable collection of Rockingham ware and Mr. O. Mason gave me valuable information when I saw him at his firm’s premises in High Street. He quoted some of the very high prices which occasional examples of the Brameld family’s pottery had fetched, and when showing me some exquisite specimens of Rockingham monkey vases, pointed out the gilt edgings. “This gilt never tarnishes,” he said, “and it is supposed that the Bramelds melted down guineas to make it’.

Of the William IV. dessert service Mr. Mason said that the Bramelds submitted several designs for royal inspection, and of these “test pieces” he has two specimen. Despite strong competition the Swinton pottery secured the contract at £5,000. Perhaps it was expected that this order would be the making of the firm, but unfortunately the Bramelds probably spent £10,000 before the work of art was finished and as a result the firm became financially embarrassed.

This service was first used at the coronation of Queen Victoria and since then only on special state occasions.

Pottery in Swinton.

Mr. William Mason has devoted considerable time and pains to the history of the Swinton works. From him I learn that the Rockingham Pottery received its name from the Marquis of Rockingham, who was succeeded by Earl Fitzwilliam the owner of the estate on which the pottery stood.

The clays used in the early days were from Swinton Common, and consisted of yellow clay used for making bricks, tiles, and coarse earthenware; finer white clay for pottery of better quality; and an excellent clay for making fire bricks. The materials used for the porcelain body were Cornish stone and china clay from Cornwall, flint from the Sussex and Kent coasts, Dorset clay, and calcined bones.

Rockingham Ware.

From 1787 to 1800 the Firm traded as become s `Greens, Bingley, and Co.,’ some of Leeds family of Green having become partners. Late in the 18th century a peculiar kind of ware was first made at the work to the name first of brown china and then Rockingham Ware; the latter term is retained until the present. This ware is a very fine reddish-brown chocolate, and is exceptionally smooth and beautiful.

A dissolution of partnership 1806 left John and William Brameld to carry on the business, along with partners, and style of the firm became ‘Brameld and Co., Swinton Pottery’. They were later joined by a younger brothers of the family, John and William, who extended the pottery buildings, made cream-coloured ware extensively.

About 1813 the sons Thomas, George, Frederick and John Wager Brameld succeeded to control and to them, the glorious successes of the Swinton Pottery were largely due. They undertook considerable enlargements effected many improvements in the products, and introduced a flint mill.

Bramelds and Art.

Having spent considerable money in making artistic advances the firm encountered difficulties, and in 1826 Earl Fitzwilliam saved the sinking ship by advancing capital. Brameld then set himself the task of making his porcelain at least equal to any then being produced. The Pottery was altered and enlarged, and the most skilful modellers and painters available were engaged.

George Frederick Brameld applied himself to managing the continental business and for some time lived in St. Petersburg, the firm at that time enjoying considerable trade with Russia. John Wager Brameld had his elder brother’s impeccable taste and made some excellent paintings on porcelain. He was an accomplished painter of flowers, figures, and landscapes.

Thomas Brameld lived in the old Swinton House and died in 1850 and before 1854 his two brothers were buried along with bird at the north side of Swinton Churchyard.

When the works were closed by the Bramelds in 1842 a small portion of the Pottery was taken over by an old and experienced workman, Isaac Baguley, and his son, Alfred, succeeded him at his death. Baguley did not manufacture the ware himself, but decorated what he bought from other firms with marked taste.

And that was the end of Swinton as an internationally recognised pottery and china ware centre.